Workers acting union drives social and economic equality.

Driving economic equality

Those countries with a higher density of trade union membership have lower levels of economic inequality. Union workers engaged in collective bargaining backed by a meaningful right to strike drives economic equality on two-levels.

First, it moderates wealth inequality through driving an increase in labour’s share of national income. That is not to say that collective worker activity is the only driver of the respective income shares of labour and capital, but I am asserting that it is one of the key drivers, and its impact is visible over time.1

Second, union workers act to rebalance income inequality by driving up the wages of the lowest paid workers more specifically, and curtailing wage growth for the top-income bracket such as senior managers and executives.

Union workers act collectively as a brake on capital’s natural tendency to produce growing wealth inequality. As discussed in a previous post, Australia’s regime of state control of worker-association and falling trade union density have correlated with a shift of relative national income shares from labour to capital. I estimate this intensified extraction from workers as roughly equivalent to a AUD$20,000 poll tax that each household is paying directly to the oligarchic class in Australian society from lost wages.

There is good reason to believe that this goes beyond mere correlation.

Internationally, there is clear data that shows countries who have higher density of trade union membership have a lower Gini coefficient.2 For example, New Statesman analysis of Gini coefficient data and trade union density, freely available at the World Bank and the OECD, highlights exactly this point. Saywah Mahmood writes that “many Nordic countries have far lower inequality and higher trade union membership.”3

One of the key causes, therefore, of growing wealth inequality in the Anglophone world since the late 20th century is a concerted and deliberate effort by the political and economic elite to smash working-class organisation.4

Inequality can be read not just in accumulated wealth but also in income. The democratic DNA at the heart of workers acting in union also drives income equality.5 The greater number of workers acting in union then the higher the pay of the lowest paid workers, and the lower the pay of the highest paid.

It’s a natural outcome of an extension of the realm of one worker, one vote decision-making when it comes to the economy. An April 2021 article in The Quarterly Journal of Economics entitled “Unions and Inequality over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data” found consistent evidence in US economic and household data going back to 1936 that unions reduce income inequality.6

Union activity, whether directly through collective bargaining or indirectly through pushing such policies as an increased national minimum wage, sets a dignified floor for all workers. Conversely, the absence of union activity and organisation enables a culture of corporate impunity that allows executive pay to rise beyond any semblance of merit.

One might argue that economic inequality is the social price for living in a prosperous free-market economy. Humans, however, are social creatures and inequality weakens the social bonds of cooperation that hold us together. As full humanity is realised in communion with other people, inequality injures us all. The myth that a person can ever truly thrive as people suffer around them is an offensive notion that future generations will regard as one of the horrors of our present age.

There is strong comparative data to suggest that a greater level of economic equality between rich and poor, independent of total material income, has a positive impact on a range of social outcomes.7 This goes for such diverse indicators as social trust, gender equality, violence, crime, longevity, international solidarity, educational attainment and more. Greater economic equality drives overall community resilience and quality.

Unions driving social equality

Union workers not only directly struggle for such issues like gender equality and international solidarity but the impact that organised workers have on income and wealth through the social driver of collective bargaining also creates a social climate that is more conducive to these social outcomes. The autonomous activity of workers can motor a positive feedback loop for human equality.

Meanwhile, the cost that the oligarchs impose with their privilege is paid not just in money but in kind through a degradation in the very quality of all our lives.

Labour unions are a powerful countervailing force for social equality.

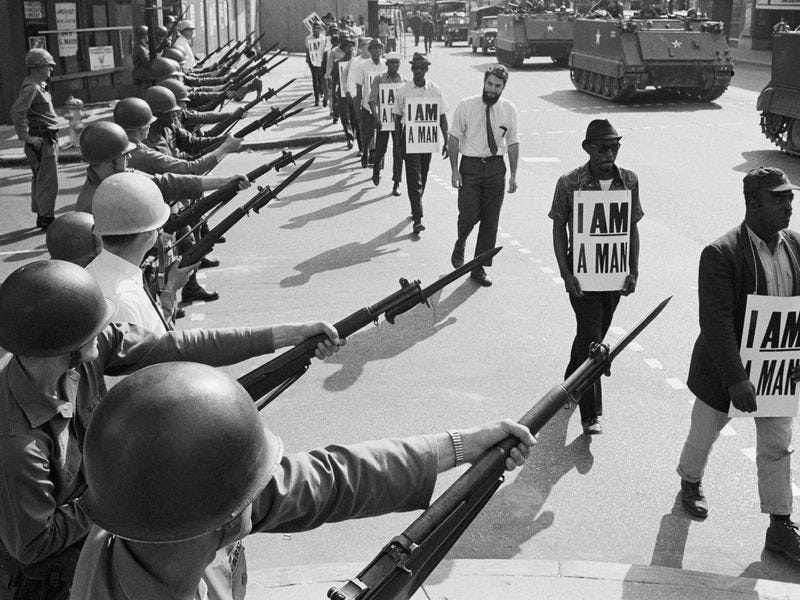

I write this with confidence despite the many historical examples of union workers acting to perpetuate or entrench forms of social inequality be it racism, sexism or some other form of social hierarchy.8 The role of the Australian trade union movement in seeking to regulate the price of labour through instituting the White Australia policy to restrict immigration on racial grounds, is a disgraceful stain on the legacy of the country’s labour movement. It is a historical wrong, and a failure of strategy, that has consequences for the present moment.

Moreover, many male trade union leaders in the 1960s actively fought against the push on the part of feminists and unionists to win the vital principle of equal work for equal pay.9 These are two clear examples of at least some sections of the union movement actively working to preserve forms of social hierarchy and privilege. Yet, I write with confidence on this matter because the democratic relation at the core of the trade union form pushes for social equality over time. This is not to assert that strong unions by themselves are sufficient to grapple with racism, sexism and other forms of social chauvinism. No, unions are made of people, and people can get things wrong and are generally products of the social context that they find themselves in.

Workers, however, actively working to organise into a union have to confront social hierarchies and oppression in so far as they are present in their workplace and a barrier to advancing their common interests. Active participation in the class struggle itself presents opportunities for workers to transcend prejudice.

Often unless workers can build relations of mutual trust with their co-workers based on a recognition of each worker’s dignity, they cannot move their employer. Workers in unions can transform the mundane solidarity that binds people in a singular social group or category imposed by the elite into a transformative solidarity that traverses categories of difference across the working class.

This relation of worker-to-worker trust across diverse social groups can then directly and indirectly push back against social inequalities. The role of workers organised into unions pushing up the wages of the lowest paid workers, as previously discussed, also impacts on social equality. It is why the collective activity of union workers sets up a sort of positive feedback loop as far as economic and social equality goes. The two rise or (as we see in the present conjuncture) fall together.

Generally it is the newest entrants to the labour market such as recently arrived migrants, young people and parents (mostly women) returning from long-term caring responsibilities who occupy many of the lowest paid jobs in a workplace. Increasing the pay and voice of these workers increases overall social mobility and the immediate economic plight of many of these social groups, thereby, preventing further entrenchment of some forms of social inequality and providing workers greater capacity to tackle directly entrenched forms of discrimination and disadvantage themselves.

I am hoping to feature future guest posts on those directly involved in various struggles for equality too. For now, however, I will detail what I have witnessed.

Warehouse work: exploitation feeds further inequality, workers resistance pushes back

Take an ordinary non-union Australian warehouse of 50 or more workers, and the impact of a group of well-organised workers on social inequality becomes quite stark.10

Under Australia’s enterprise bargaining framework, an agreement does not automatically apply to every worker conducting the relevant work, occupations or tasks in the workplace but only those who are employees of the host employer.11 Well-organised workers (regardless of their employment status) can win a struggle in a legally, economically and ideologically contested space to formally or informally regulate the pay and conditions of all workers under one roof. It is a struggle, however, that takes on a terrain greatly weighted in capital’s favour.

What this means in an ordinary unorganised or partially organised warehouse then is a relatively small group of forklift drivers who are more likely to be engaged directly by the employer. These workers are in turn more likely to be older, white and male. They will generally get paid some level of above-Award wage. Then there are a greater number of pickers. These workers will be running around on foot engaging in manual labour through picking orders off warehouse shelves and carting them to a specific location for orders to be dispatched.

Given the greater physicality of pick work, the tendency to be running around on foot in forklift traffic zones, and the lack of driving or mechanical operation means the work is regarded as lower value. It is also one of the more physically dangerous workplace activities. Pickers are far more likely to get a physical injury including life-long back injuries from the repetitive strain. It is, therefore, far more cost effective for corporations to burn and churn these pickers using labour hire agencies compared with investing in more sustainable labour practices.

This is the hidden cost born by some of the most vulnerable segments of the working class in the name of consumer convenience. Senior human resources executives of one of Australia’s major supermarket chains have openly described their logistics labour management strategy to NUW leaders in the late 2010s as “sweat the box”. So, who are these pickers?

These pickers are more likely, compared to the forklift drivers, to be younger, female and ethnically and linguistically diverse. It is not uncommon in warehousing for these workers to be stuck in labour hire arrangements that are paid less than permanent workers doing similar functions as their rates of pay will be based on the legal minimum at best. Another widespread experience for these workers is that they will get paid an entry-level classification when they may actually be entitled to a rate of pay at a higher classification.

The sum total impact of this arrangement in the Australian logistics industry is that capital’s quest to “sweat the box” re-imports social hierarchy into the warehouse—one where social characteristics are at a minimum loosely correlated to workplace privilege—but in a seemingly more socially acceptable manner using the discourse of workplace “flexibility”.

The socially corrosive consequences of these workplace arrangements are far more apparent when you are in one of those warehouses. It is not unusual, for instance, that labour hire workers, often but not exclusively recent migrants and immigrants, will wear a different colour high vis vest or uniform to permanent warehouse staff. They might not get access to the same lockers. There was even a case where labour hire workers had to use different staff toilets. These same workers are regarded as doing the “shit jobs” by the permanents. It creates an indirect form of apartheid.

Moreover, given the injury rates, the fact that shifts are often issued by text message, and the reality that the most mild so-called indiscretions (from leaving work to look after a sick kid or calling in sick yourself) get you booted from the workplace, it is quite a challenge to organically build relations of solidarity between groups of workers. This is especially so, as a high rate of turnover means these labour hire workers might be different people from one week or day to the next. This can create a culture where permanent staff do not think it is even worthwhile to say hello to or learn the name of labour hire workers they might not ever see again.

In the absence of worker solidarity springs division and prejudice. It is all too easy for a worker who associates a group of relatively individually anonymous workers from particular cultural groups with a “shit job” in their workplace to then ascribe the quality of “shitness” to that cultural group.

In the absence of worker solidarity springs division and prejudice.

This cognitive slippage is compounded by the fact that the hyper-exploitation of insecure workers is then used to attack the living standards of relatively privileged workers even while their relative position is maintained. This could mean anything from putting the pressure on permanent workers to increase the pace of work, using the example of insecure workers to hold down the pay of directly engaged permanents or just managing out permanent staff and replacing the workload with casual labour.

Without a solid class analysis of who is benefiting from this increased squeeze on workers and why, it is all too easy for one group of workers to then blame another group of workers for this outcome. Most workers will resist this cognitive slip between “shit jobs” and “shitness” but it only requires a minority to slip in this manner for it to have considerable social consequences, especially where this racist minority are organising and the rest are not.

Much like algae blooms in stagnant waters, so too does prejudice flourish where workers are passive.

Thanks for reading The Solidarity Wedge! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support this project for union renewal.

This post is located within the first chapter within the first of three parts for the overall project. Part One is Solidarity as Strategy and takes a broader view of solidarity and how it can still emerge within and against a fundamentally inhumane system. Use the about page to locate where you are in this broader project.

Of course, the taxation system is a powerful means with which to drive economic equality separate from collective bargaining but even then the capacity of a politically sympathetic government to use this lever is also influenced by the relative power of workers.

The Gini coefficient is a way to measure the relative equality of the distribution of wealth or income. A measure of 0 represents a state of perfect equality, whereas a measure of 1 means 1 person owns all wealth or income.

See https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/economy/2022/12/countries-high-trade-union-membership-equal-gini-coefficient

See for example Melinda Cooper, Counterrevolution: Extravagance and Austerity in Public Finance (2024), Zone Books.

See https://journalistsresource.org/economics/inequality-labor-unions/ for further.

See for example the research and resources available at The Equality Trust https://equalitytrust.org.uk/research

For a highly readable history of how unions have both acted to entrench social privilege and driven social equality in Australia during the 20th century see

’s No Power Greater: A History of Union Action in Australia (2025).I imagine there is a significant amount here with any decentralised (that is workplace by workplace) labour relations regime.

This remains the case with the Same Jobs, Same Pay reforms of the Albanese Labor government in Australia. It is unknown, at the time of writing, as to whether the ability of unions to seek equal pay orders may impact this relational dynamic. I would expect that much depends on how workers actually organise, and thus the impact of a legal change cannot be predicted solely on an analysis of it in the abstract.

Thank you again for more continuity about strategy and unionism. I will try for a longer comment on this chapter about equality while recommending others to read it and join your discussion. In brief, for now, it is worth working out the “type” of unionism that leaves inequality intact, unthreatened, even though there might be marginal improvement. Some unionism is compliant. We have had that in the history of our movement and it remains albeit in a different form. One impact of neoliberal and neolaboral industry and workplace industrial laws is the multi fragmentation of wage rates. That has not been studied or discussed in Australia to my knowledge. I am happy to be corrected. The origin of inequality in income and then wealth lies in the exploitation of the workforce during both the “working day” and then the “reproducing labour time” that is necessary for that working day. Although the details are different, the continuity with the days when unions were first being “invented” is the same. Finally, how unions are developing in developing countries is quite profound: there is a contest between original unionism and its distinctive combativeness, compliant unionism, and euro-centric unionism.