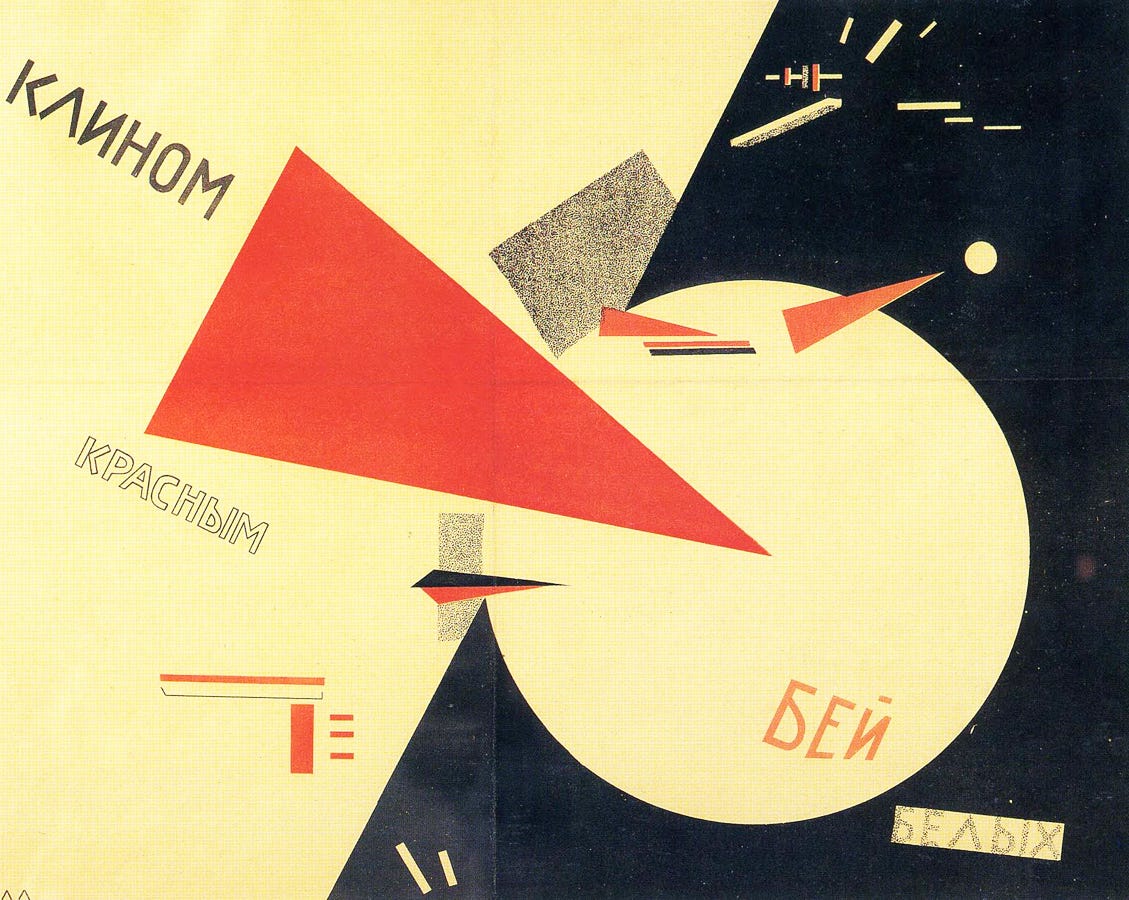

Rebuilding worker power: the Solidarity Wedge and the three fronts of class struggle

Chapter Two: The Solidarity Wedge Part III

Based on my experiences as a union leader, I will attempt to cohere these insights into a three-pointed strategy I call the solidarity wedge. The union movement’s struggle should be thought of as having three points each connected and underpinned by relations of solidarity.1 For as Tom Mann wrote, worker solidarity is “[t]he preliminary essential condition” for class power.2

The Workplace Struggle

The first front facing point is the industrial or workplace struggle. This is where most workers spend most of their time. It is where the single biggest opportunity for daily cooperation exists. Moreover, given capitalism depends every day on extracting value from the wage-labour relationship, disruption on this point temporarily slows down or halts the system as it actually exists. To put it another way, collective action on the job between workers opens the space for a radically new world to be born even as by itself it cannot guarantee the birth of this new world.

For that space to be filled, however, requires the broader scope and vision that the other two strategic points provide for workers—that is worker ownership and politics.

The Struggle for Worker Ownership

By worker ownership I mean prefigurative examples of organisations and enterprises being owned and managed on a one worker, one vote basis (or a one person, one vote basis when considering points of consumption for wider community needs). These spaces can be relatively small compared with the size of corporate oligopolies. That does not matter. Scale is not a universal strategic good even as it is a necessary objective for the next wave of unionisation. An uncritical adoption of scale can reflect the internalised logic of capital—existential growth forever—and obscure the strategic necessity of the need to focus on specific relations between workers.

The strategic point of this pole is to provide concrete examples of social functioning beyond the organising principle of managerial direction as well as fostering a culture of solidarity with less dependence on corporate rule. It points to a future where every worker labours free from the control of others.

This should raise worker expectations as far as claims and struggles go within workplace and political organising while also building up a non-corporate support and welfare structure for militant workers. This builds overall resilience for inevitable setbacks and defeats. Even within the strictures of a capitalist system, there is no reason why this pole cannot grow in significance over time.3 For instance, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, cooperatives account for a significant 30% of GDP.4

The Political Struggle

The final point of the solidarity wedge is politics. By politics, I mean more than the decisions of parliamentarians and elections for parliament but rather the broader direction and shape of the social community. The former assumes that decisions are made by someone else—a definitionally narrow class of an elected few whose range of decision-making is simultaneously structured and limited by capital’s privilege within the system. Politics is the art of the possible under capitalism whereas worker-to-worker organising is an effort to change power relations so as to make the socially necessary actually possible. Politics must be a fundamental part of union strategy but it should grow out of, and remain rooted in, workplace organising.5

Control of the state is necessary for system change but alone insufficient for the objective. It requires an activated mass to put a narrow class of representatives both in government and keep them connected to their needs when capital’s inevitable backlash arrives. A movement, therefore, based on the authority of elected representatives is fundamentally vulnerable.

Being in government is not the same as being in power. This is a matter of the utmost strategic importance.

Defining politics, however, as about that which concerns the direction and shape of the social community, opens up the strategic possibility of direct worker involvement in the political field.6 Beyond running for parliament or volunteering in an election this includes, but is not limited to, joining a political party organised around pro-worker values, engaging in an ongoing struggle about the priorities, values and policies of that party, participating in broader public discourse, community organising, engaging with local government and taking forms of direct and collective action on social and political issues such as the Italian union movement’s strikes for Gaza.

The simplicity is the point

There is nothing greatly original in the ideas of workplace organising, building cooperatives and mass political participation. The simplicity is the point. A good strategy, more often than not, is a simple strategy.

This is because a good union strategy should be open to the broader membership (this is not to take away the operational requirement at times for confidentiality such as in the early days of an organising drive). Simplicity and openness works not because ordinary people are inherently immature but rather because it facilitates democratic cooperation between workers.

This strategic openness provides space for disconnected organisers and unionists to work towards a common goal without direct communication, and as such may also be useful in a more authoritarian configuration of the political economy.

The solidarity wedge can be summarised as workplace power, worker ownership, and political action – easily explained in 30 seconds, in short asides on the shop floor, or while making coffee in the lunchroom. It means more workers can take ownership of the strategy, hold official union leadership to account for prioritising the solidarity wedge in their work or take it on themselves to meaningfully further this work even with limited direct communication with many other workers.

Keeping this strategy secret from the political and corporate elite will in no way be the ultimate decider of its success or failure otherwise.

The unoriginality of these three points is also deliberate. Organising for workplace power to achieve better wages and conditions to live, building democratic institutions of mutual and social support, and collectively intervening in the political process are all as old as the labour movement itself.

Each point speaks to a different necessity to be overcome if we are to find a way through and beyond the almost totalising social system that is capitalism. The hard task, strategically speaking, is not in finding entirely new ideas for the labour movement but being creative about when and how to meaningfully make progress on these three points in the current context.

Further, drawing out these three points posits a dynamic relationship that is both constructive and ultimately complimentary. The labour movement needs the capacity to change direction as swiftly and seamlessly as a flight of cranes without giving up the integrity of any pole. One of the key points of this work, and not that I claim any original invention over, is to draw out a specific strategic relation between each of the three points.

Each point is connected in struggle

Sustained success at any one point depends on some degree of progress and security of position coming in the other two points. In the long-run each is important. At a given future point, however, it can be harder to prioritise exactly where each point stands relative to the others. Conceiving of the three poles as connected in a wedge formation, however, at least holds out the possibility of productive organising which emerges from combinations of two or more poles.

Organising for ownership and political organising could fuse in an organising campaign around how local government and its attendant anchor institutions, such as hospitals and universities, nurture worker cooperatives in their procurement policies.

Political organising and workplace organising may blur around a direct ballot measure on minimum wage rates.

Workplace organising and organising for ownership can potentially coalesce within a collective bargaining claim to set up an employee ownership trust structure within an enterprise.

The three poles exist within a state of mutually reinforcing interdependence or they fall apart. This interdependence between the three points is evidenced in the neoliberal reaction itself, which involved a common agenda of de-unionisation, privatisation and de-mutualisation. Growth of worker-owned firms at scale requires a state that is orientated towards and supportive of the sector. A truly left reformist government can make far more progress on an ambitious policy agenda where there is an organised mass base in civil society and industry supporting its work. Workers will have greater confidence to take action where there is a government committed to full employment or a worker-owned social support structure in place from housing to utilities.

Each point in the solidarity wedge can act to reinforce the other two points of struggle where it works to strengthen the underpinning relations of solidarity between workers.

For the solidarity wedge to work, it needs organised workers to move and change directions as rapidly as a school of fish (both in terms of which pole may take the leading edge, and how it takes the leading edge) in the face of an adaptive elite. If the global mass protests and rebellions of the 2010 teach us anything, it is that the global elite are capable of adapting to any tactical innovation on the part of the people.7

This requires social organisation that is infused with the structured and democratic problem solving capacity of broad layers of workers. This cannot happen organically or by accident, it requires more and more unions and organs of organised labour to embrace the critical education of rank-and-file workers informed by the pedagogical philosophy of Paulo Freire.

This is how the theoretical struggle becomes directly embedded within and connected to the economic struggle.

A more generalised embrace of critical education within sections of the labour movement is a precursor to the implementation of the solidarity wedge and its continuing relevance as a dynamic strategic framework. It is, also no accident, that a common theme of any democratic reform challenges to existing union administrations is often a critique of the paucity of delegate and member education.8

At the beginning of this chapter, I outlined the need to place workers organising on the job as the leading point of the solidarity wedge. The reason for this is simple. The workplace is where workers have a lived experience of the brutal reality of capitalism that cuts through the structuring myths and stories that form the common sense on which the system depends.

The workplace is where most latent and potential power from day-to-day worker cooperation lies. If power, after all, is based on person-to-person cooperation then the fact that most adults spend most of their waking lives at work means this is the single biggest source of latent working-class power. The fight begins where we find the people.

Worker-owned enterprises by themselves are too small in the Anglophone world and take too long to build to work for system change on their own. As part of a broader strategy, it is a different matter, as a small but effective worker-owned sector can inspire the actions of millions.

Politics, devoid of an organised mass base, degenerates into a contest between elites where ordinary, and largely atomised, people either disengage or consume as entertainment passively supporting one side or the other for diffuse reasons related largely to one’s perceived identity. Such atomisation leaves people vulnerable to predation by an authoritarian, even totalitarian, elite.

Just as the breaking of relations of solidarity was key to the decline in union power from the 1980s onwards, so is the nurturing of solidarity central to effective union strategy.

I write of solidarity, therefore, not just as a core union value or principle but for its pressing and urgent strategic necessity. Solidarity animates this strategy, and solidarity will end up fuelling a new democratic and socialist society.

A union, as previously discussed, is a relationship of mutual support between workers to advance their shared interests. It is a way of workers cooperating together for their common benefit. It just so happens that power grows from such relations of cooperation. Solidarity becomes a means to actually build power to win.

The urgent question of our atomised times is not so much “what is to be done?” but rather how can relations of active solidarity be nurtured in the wreckage of an increasingly authoritarian late capitalism?

This post is located within the second chapter within the first of three parts for the overall project. Part One is Solidarity as Strategy and takes a broader view of solidarity and how it can still emerge within and against a fundamentally inhumane system. Use the about page to locate where you are in this broader project.

Alternatively, this can be conceived as the economic pole within the three-pointed struggle for socialism itself having three points.

Thomas Mann, The Way to Win: Industrial Unionism, Barrier Daily Truth Press (1909).

Time being the operative variable here given the ongoing crisis of capitalist production on social-ecological reproduction.

John Duda, “The Italian Region Where Co-ops Produce a Third of Its GDP”, Yes! Magazine (July 5, 2016).

This is not to claim that politics generally must be subservient to the economic struggle when it comes to building a socialist future but is a more limited claim about approaching politics from the standpoint of organising within the workplace. Sometimes, there is a tendency for comrades who might otherwise agree with each other to talk past each other when looking at a matter from different levels of abstraction.

This is itself an outlook based in the Aristotelian conceptualisation of politics as it concerns any matter pertaining to the political community. This is a necessarily broad field where meaning is itself subject to struggle.

Vincent Bevans, If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution, Hachette (2023).

See Luis Feliz Leon, ““There’s a Real Fight Coming”: Newly Elected UAW Reformer Daniel Vicente on What’s Next”, In These Times (March 8, 2023). Vicente provides commentary on the relative lack of investment in member education in the UAW, this critique is more broadly applicable in my experience as a unionist.

Urgh more politics. Is the politics of the possible a nice way of saying opportunism?

https://classautonomy.info/militant-reformism-and-the-prospects-for-reforming-capitalism/

Excellent piece, as always, Godfrey. So on point, clear, and relevant.